Distributions I

Keywords

Binomial distributions

Multimonial distributions

for

Discrete random variables

Continuous random variables

Density Estimation

Model p(x) of a random variable x, given a finite set {x_1,x_2,…,x_N} of observations

Assumption: Data points are Independent and Identically Distributed (I.I.D)

Density Estimation is fundamentally ill-posed, cuz there are infinitely many probability distributions that could have given rise to the observed finite data set

Model Selection

The issue of choosing an appropriate distribution for the model

Parametric Distributions

Distributions that are governed by a small number of adaptive parameters, i.e. mean and variance from Gaussian

To determine a target distribution parameters,

In a frequentist treatment, we choose specific values for the parameters by optimizing some criterion, such as the likelihood function

In a Bayesian treatment, we introduce prior distributions over the parameters and use Bayes’ theorem to compute the corresponding posterior distribution given the observed data

Conjugate priors

leads to posterior distribution having the same functional form as the prior, therefore leads to a greatly simplified Bayesian analysis

i.e. the conjugate prior for the parameters of the multinomial distribution is called the Dirichlet distribution

the conjugate prior for the mean of a Gaussian is another Gaussian

Exponential Family

Parametric Density Estimation

Non-Parametric Density Estimation

The distribution typically depends on the size of the data set

Such models still contain parameters, but they control the model complexity rather than the form of the distribution

Sufficient Statistic

A statistic is sufficient for a family of probability distributions if the sample from which it is calculated gives no additional information than does the statistic, as to which of those probability distributions is that of the population from which the sample was taken

Binary Variables

a single binary random variable x∈{0,1}, i.e. coin flipping

x=1 <- heads

x=0 <- tails

Imagine a damaged coin that p(heads)!=p(tails), Say

p(x=1|μ) = μ

p(x=0|μ) = 1-μ

μ - parameter μ∈[0,1]

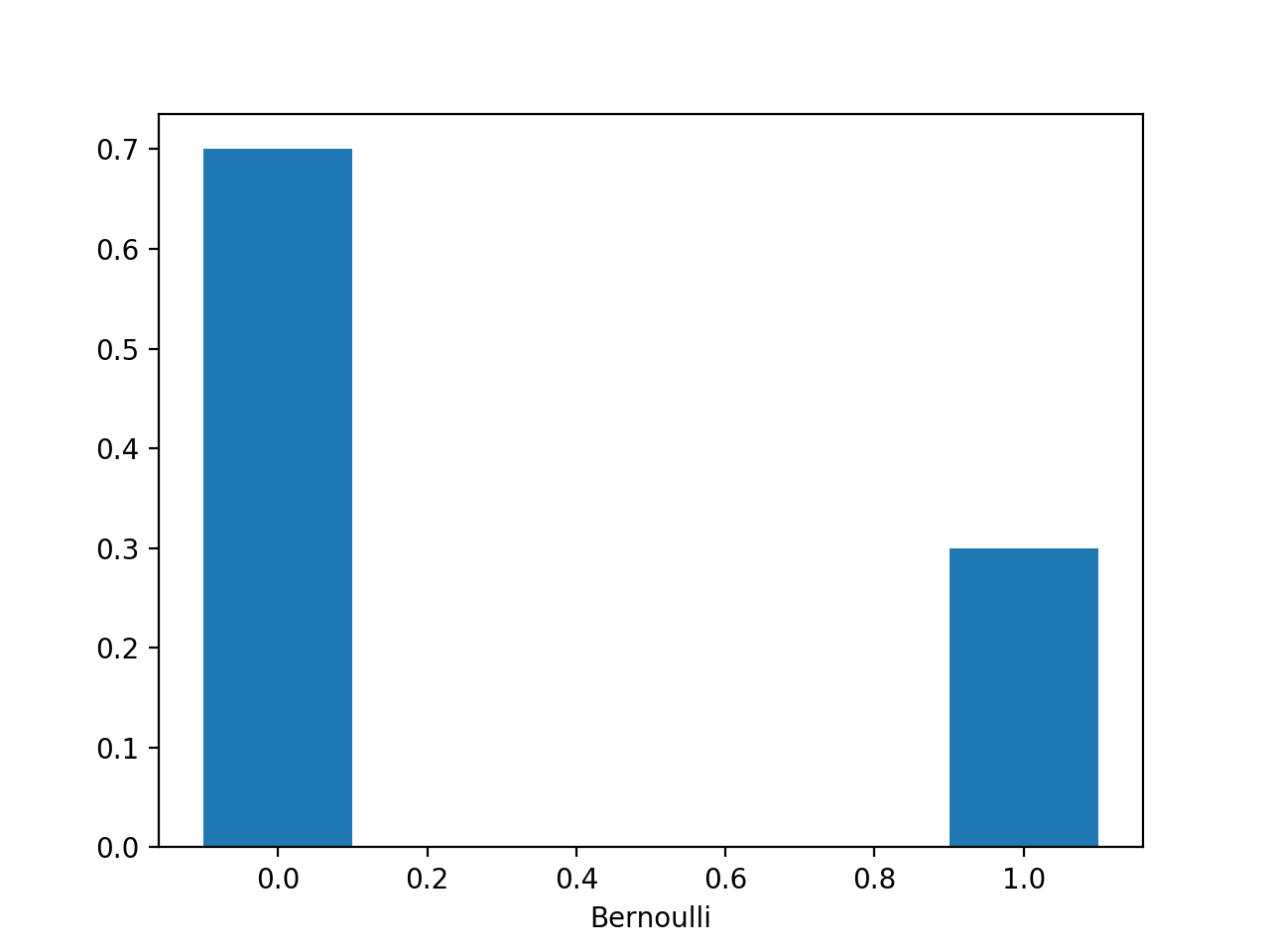

Bernoulli

Bern(x|μ) = μ^x * (1-μ)^(1-x)

is normalized

mean: E[x]=μ

variance: var[x]=μ(1-μ)

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

#hand craft

mu=0.3

plt.bar([0,1],[1-mu,mu],width=0.2)

plt.show()

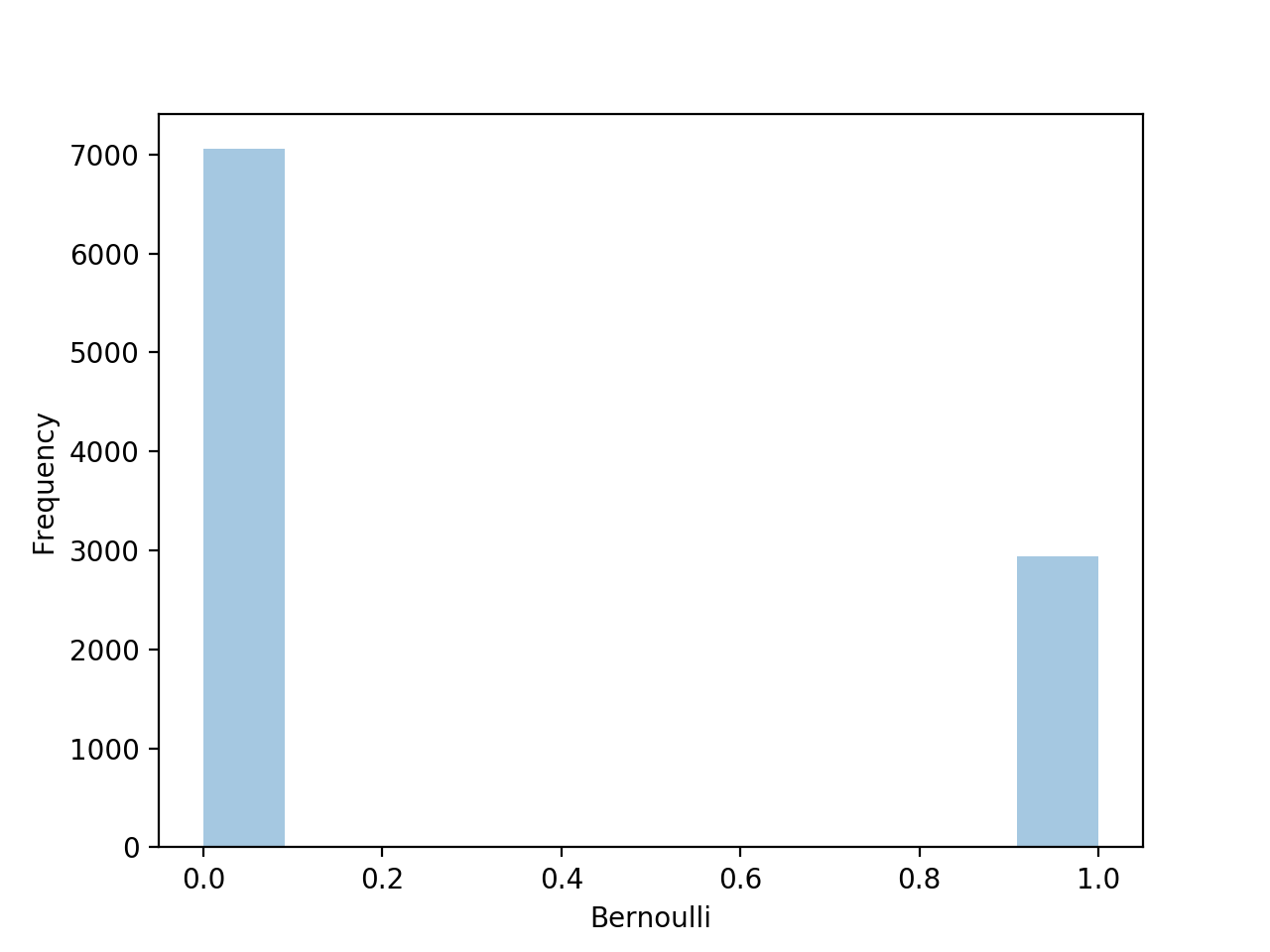

#scipy

from scipy.stats import bernoulli

import seaborn as sns

data=bernoulli.rvs(size=1000,p=0.3)

ax=sns.distplot(data,kde=False,hist_kws={'linewidth':15})

ax.set(xlabel='Bernoulli',ylabel='Frequency')

Suppose we have data set D={x_1,…x_N} of observed values of x,

p(D|μ) <- likelihood, a function of μ on the assumption that the observations are drawn independently from p(x|μ)

N N

p(D|μ) = ∏ p(x_n|μ) = ∏ μ^x_n * (1-μ)^(1-x_n)

n=1 n=1

In a frequentist setting, we can estimate a value for μ by maximizing the likelihood or the log-likelihood

ln p(D|μ) = Σ_N ln p(x_n|μ) = Σ_N [x_n*ln(μ)+(1-x_n)ln(1-μ)]

If we set the derivative of ln p(D|μ) w.r.t μ -> 0, we can have the maximum likelihood estimator

dln p(D|μ) / dμ = 0

μ = 1/N Σ_N x_n <- sample mean

ML

If we observe m ‘heads’ in the data set,

μ = m/N

ML

Problem:

Suppose, we flip 3 times a coin and happen to observe 3 heads, then

μ = m/N = 3/3 = 1

ML

In this case, the maximum likelihood result would predict all future observations should give heads

This is unreasonable, and in fact it is an extreme example of the over-fitting associated with maximum likelihood

Solution:

Introduction of a prior distribution over μ

We can work out the distribution of the number m of observations of x=1, given the data set N

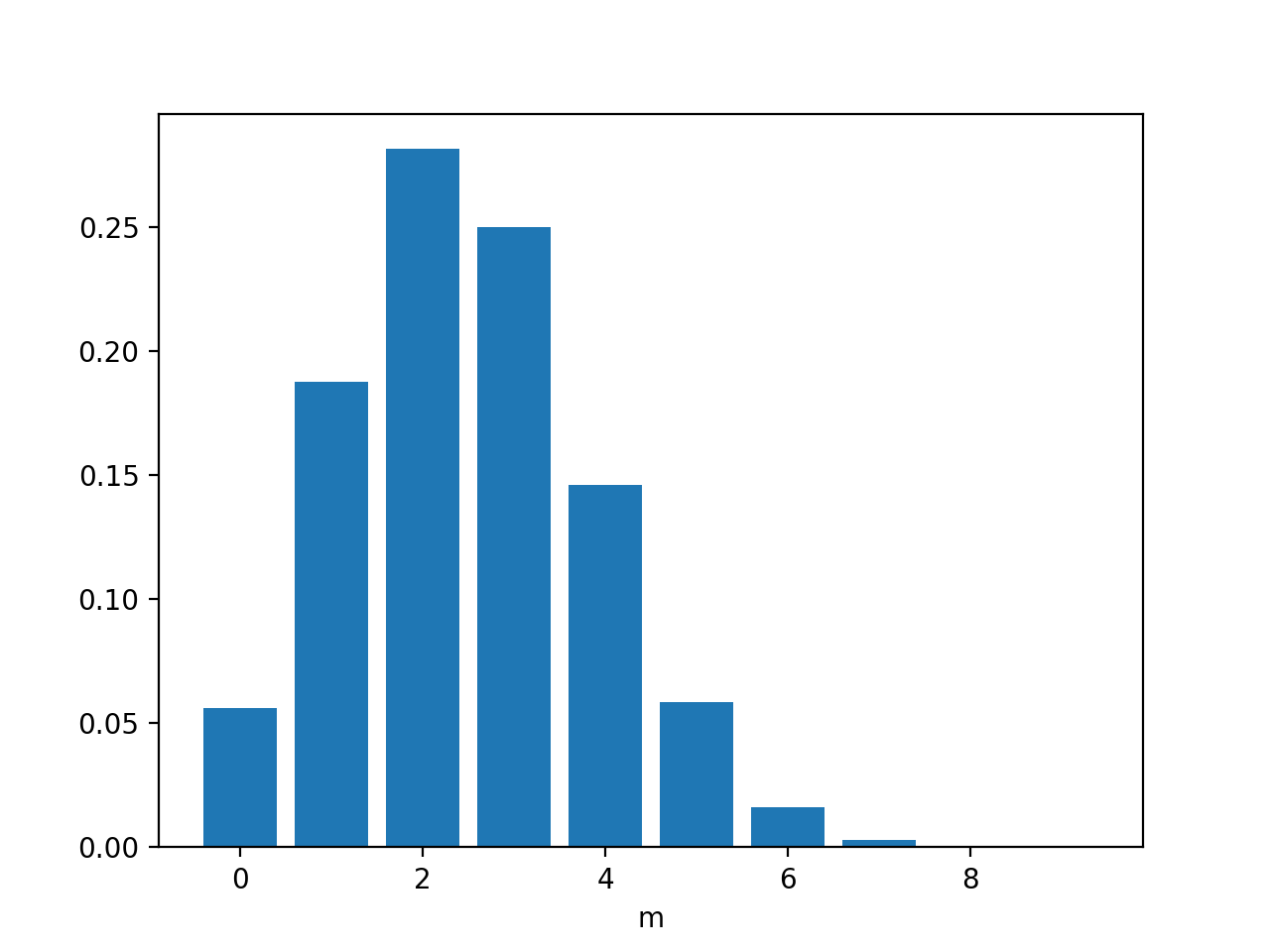

Binomial

In order to obtain the normalization coefficient we not that out of N coin flips, we have to add up all of the possible ways of obtaining m heads,

(N)

Bin(m|N,μ) = ( ) μ^m*(1-μ)^(N-m)

(m)

(N) N!

( ) = -------- <- ways of choosing m objects out of a total N identical objects

(m) (N-m)!m!

N

E[m] ≜ Σ m Bin(m|N,μ) = Nμ

m=0

N

var[m] ≜ Σ (m-E[m])^2 * Bin(m|N,μ) = Nμ(1-μ)

m=0

Say N=10, μ=0.25, (flip 10 times coin with μ=0.25, what is the probability of m heads appear)

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

#hand craft

def fact(n):

return np.math.factorial(n)

def binomial(n,m,mu):

return (fact(n)/(fact(n-m)*fact(m)))*(mu**m)*(1-mu)**(n-m)

n=10

mu=0.25

dist=[]

for m in range(0,10):

dist.append(binomial(n,m,mu))

plt.bar(range(0,10),dist)

plt.show()

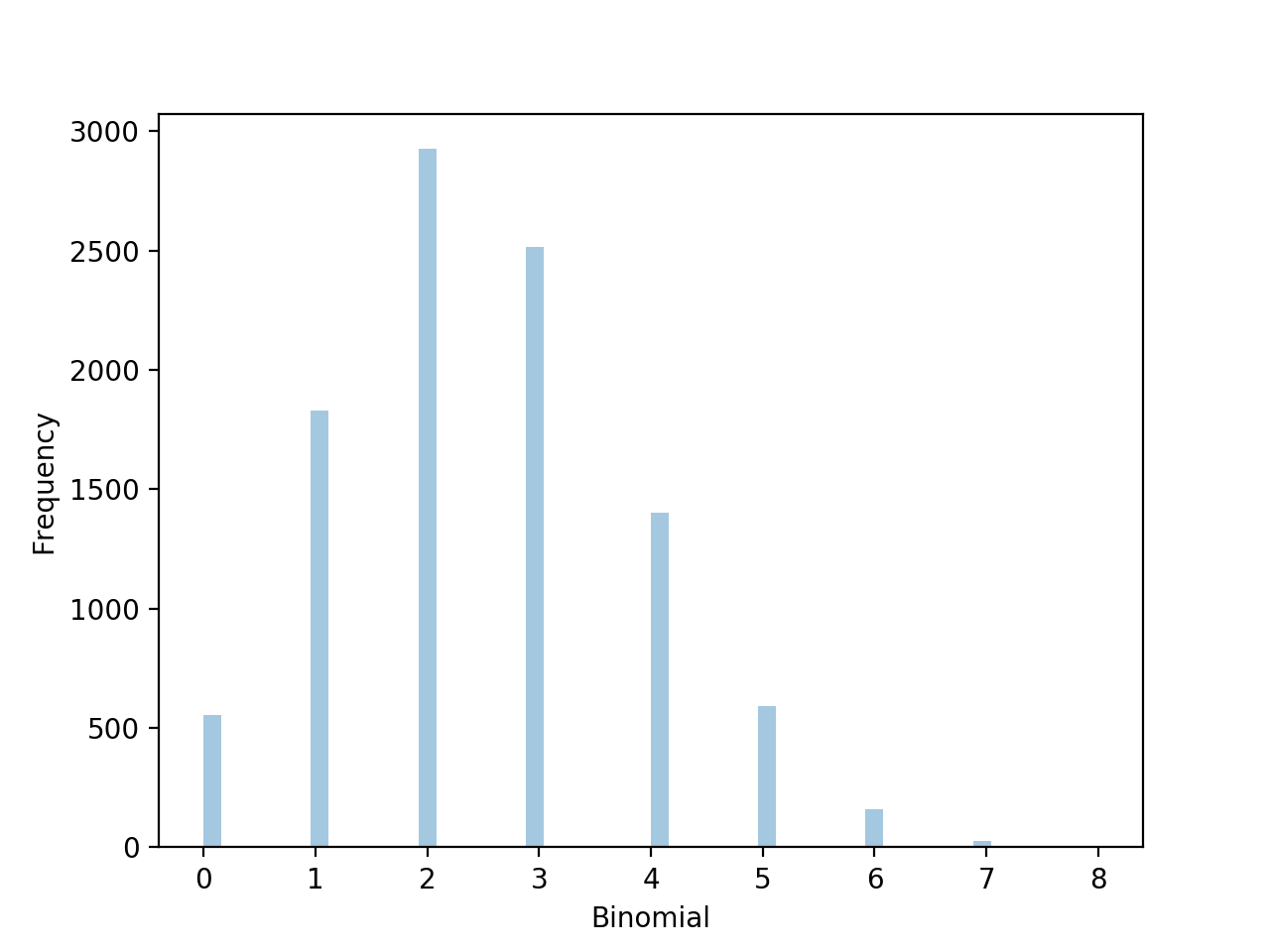

# scipy

from scipy.stats import binom

import seaborn as sns

data=binom.rvs(n=10,p=0.25,size=10000)

ax=sns.distplot(data,kde=False) #norm_hist=True

ax.set(xlabel='Binoamial',ylabel='Frequency')

plt.show()

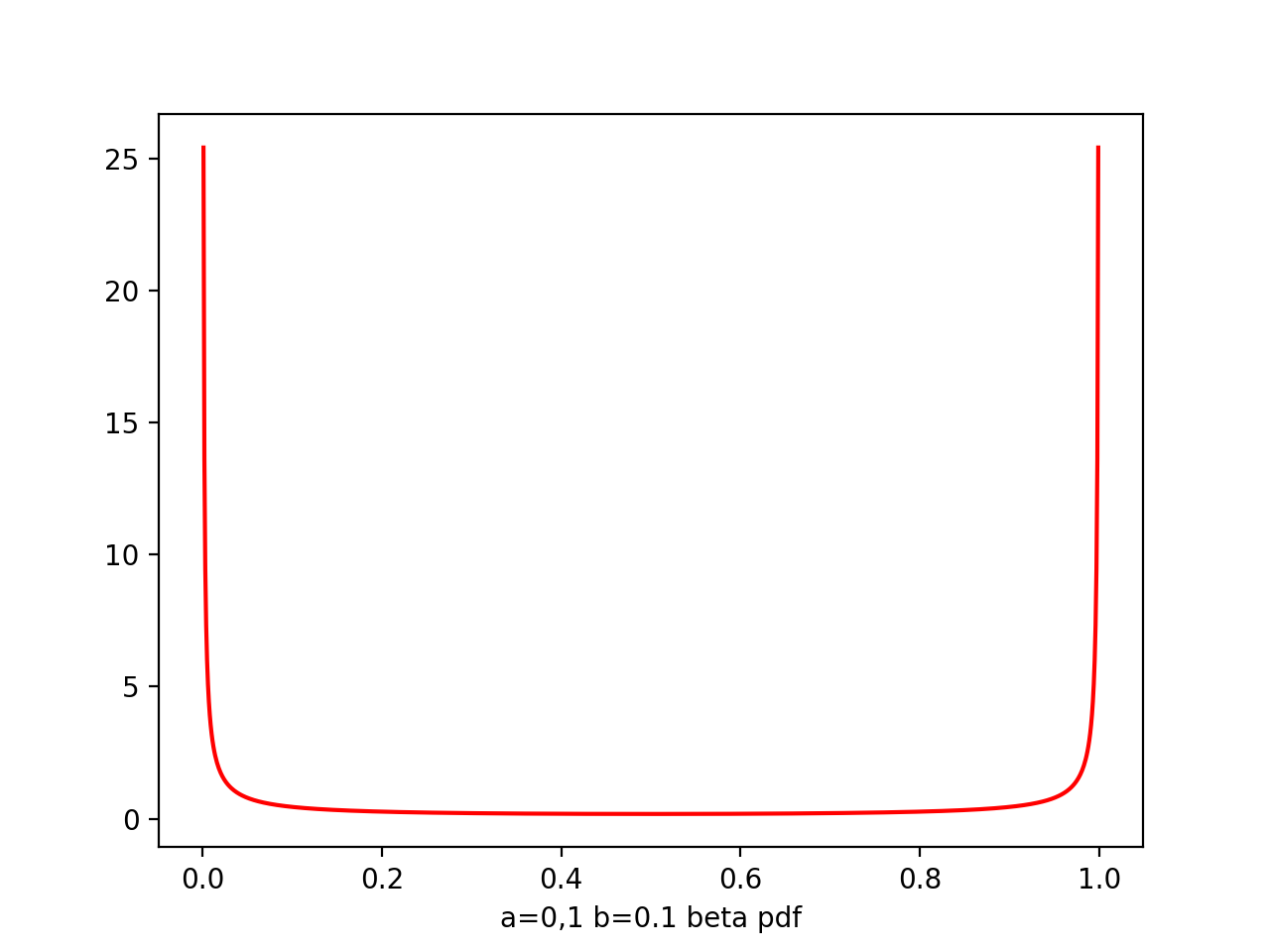

Beta

for being the prior of μ

Γ(a+b)

Beta(μ|a,b) = -------- μ^(a-1) * (1-μ)^(b-1)

Γ(a)Γ(b)

Γ(x) - the gamma function

∞

Γ(x) ≜ ∫ u^(x-1) * e^(-u) du

0

Γ(x+1) = xΓ(x)

Γ(a+b)

the coefficient --------- ensures the beta distribution is normalized

Γ(a)Γ(b)

1

∫ Beta(μ|a,b) dμ = 1

0

a

E[μ] = -----

a+b

ab

var[μ] = --------------

(a+b)^2(a+b+1)

a,b - hyperparameters, controls the distribution of parameter μ

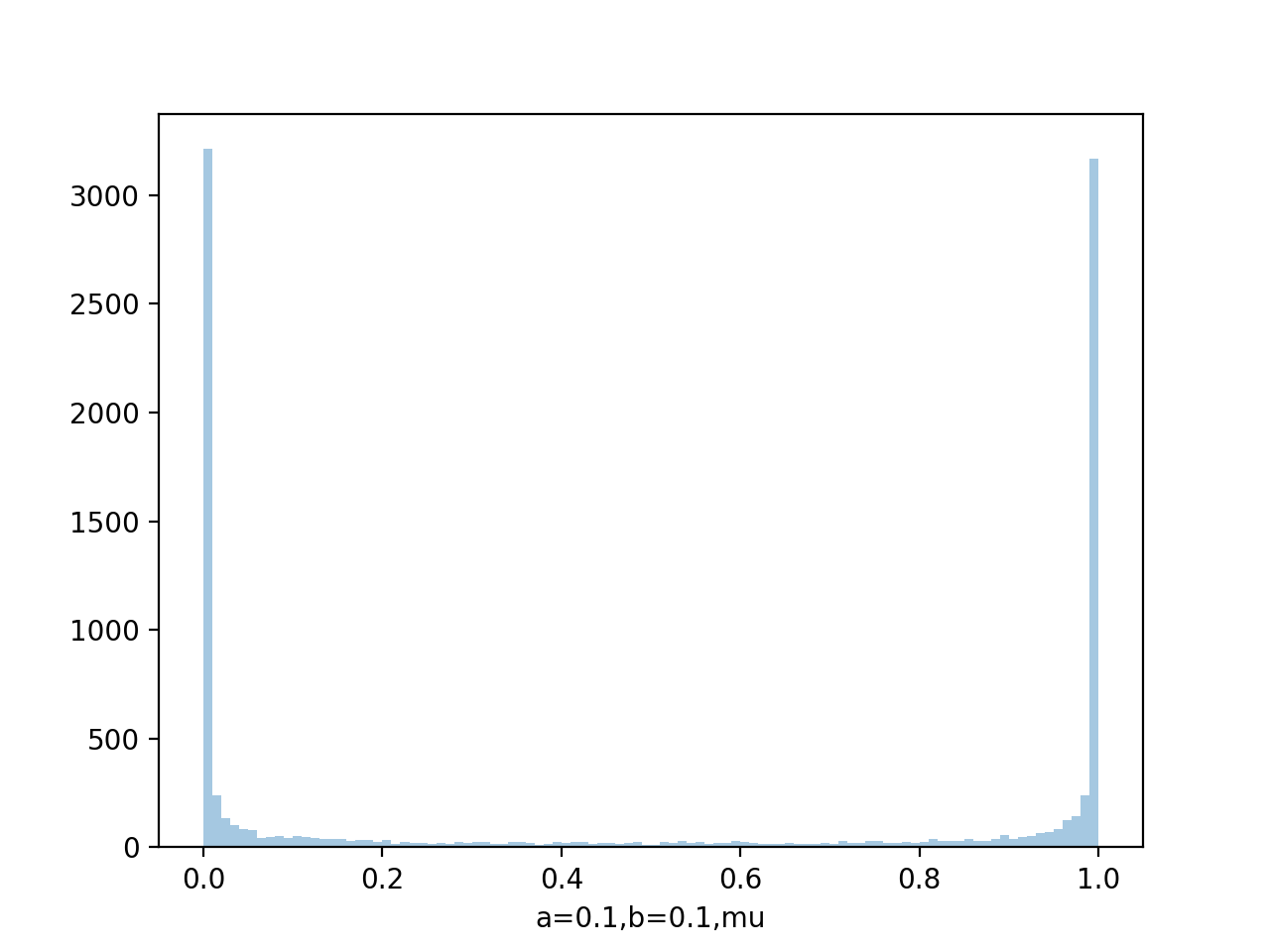

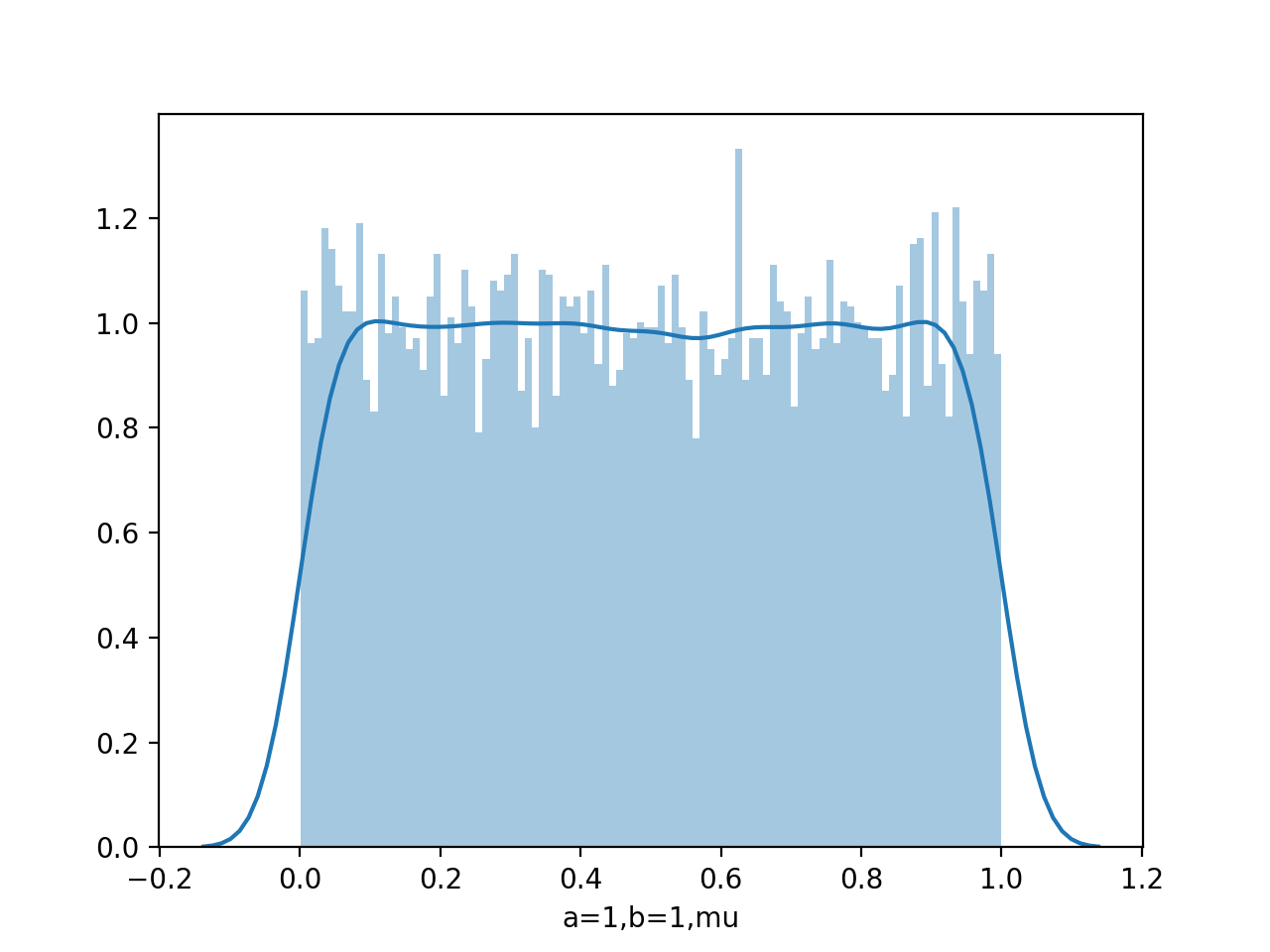

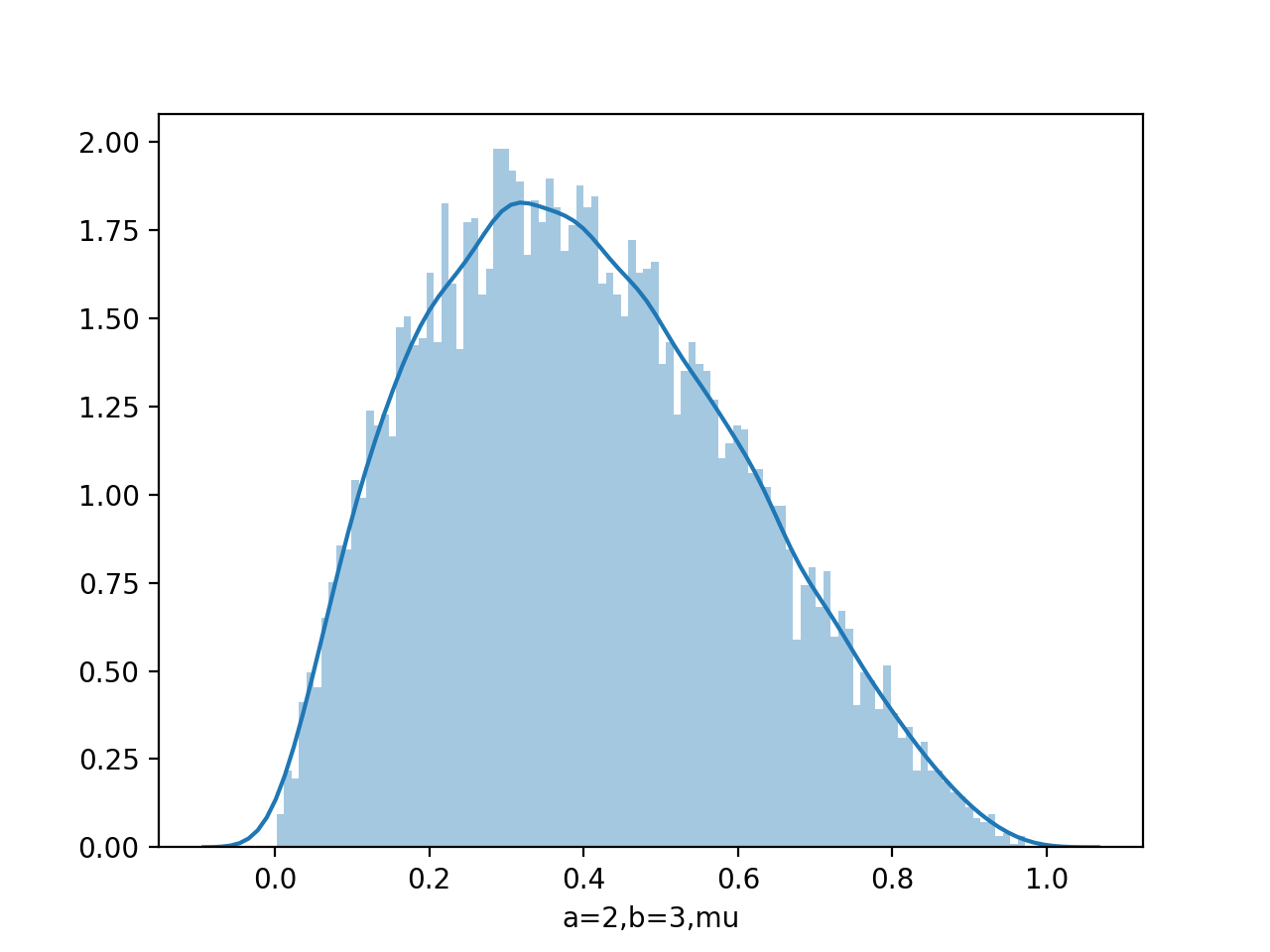

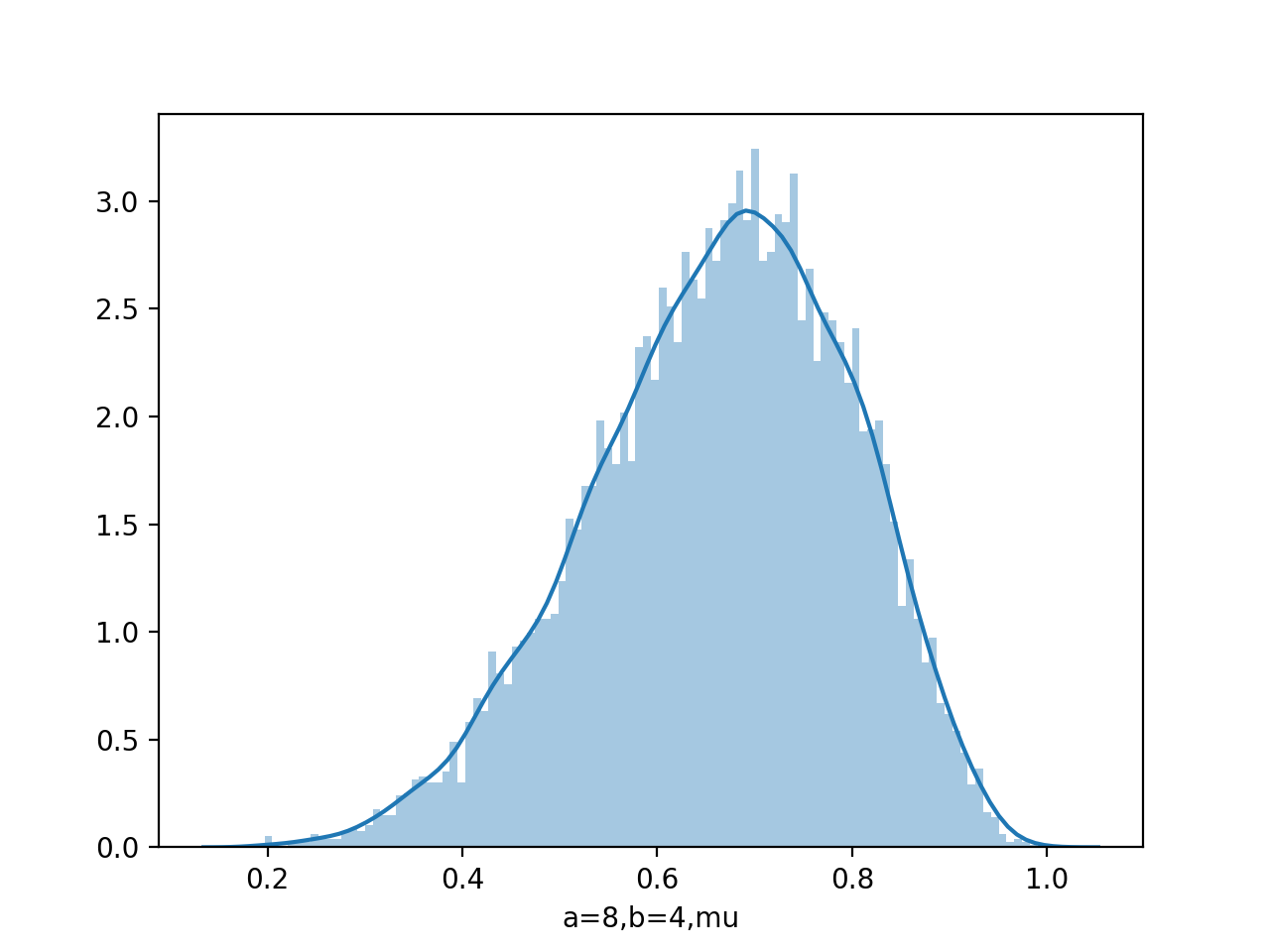

Generate data

from scipy.stats import beta

import seaborn as sns

data=beta.rvs(0.1,0.1,size=10000)

sns.distplot(data,bins=100)

data=beta.rvs(1,1,size=10000)

sns.distplot(data,kde=False,bins=100)

data=beta.rvs(2,3,size=10000)

sns.distplot(data,kde=False,bins=100)

data=beta.rvs(8,4,size=10000)

sns.distplot(data,kde=False,bins=100)

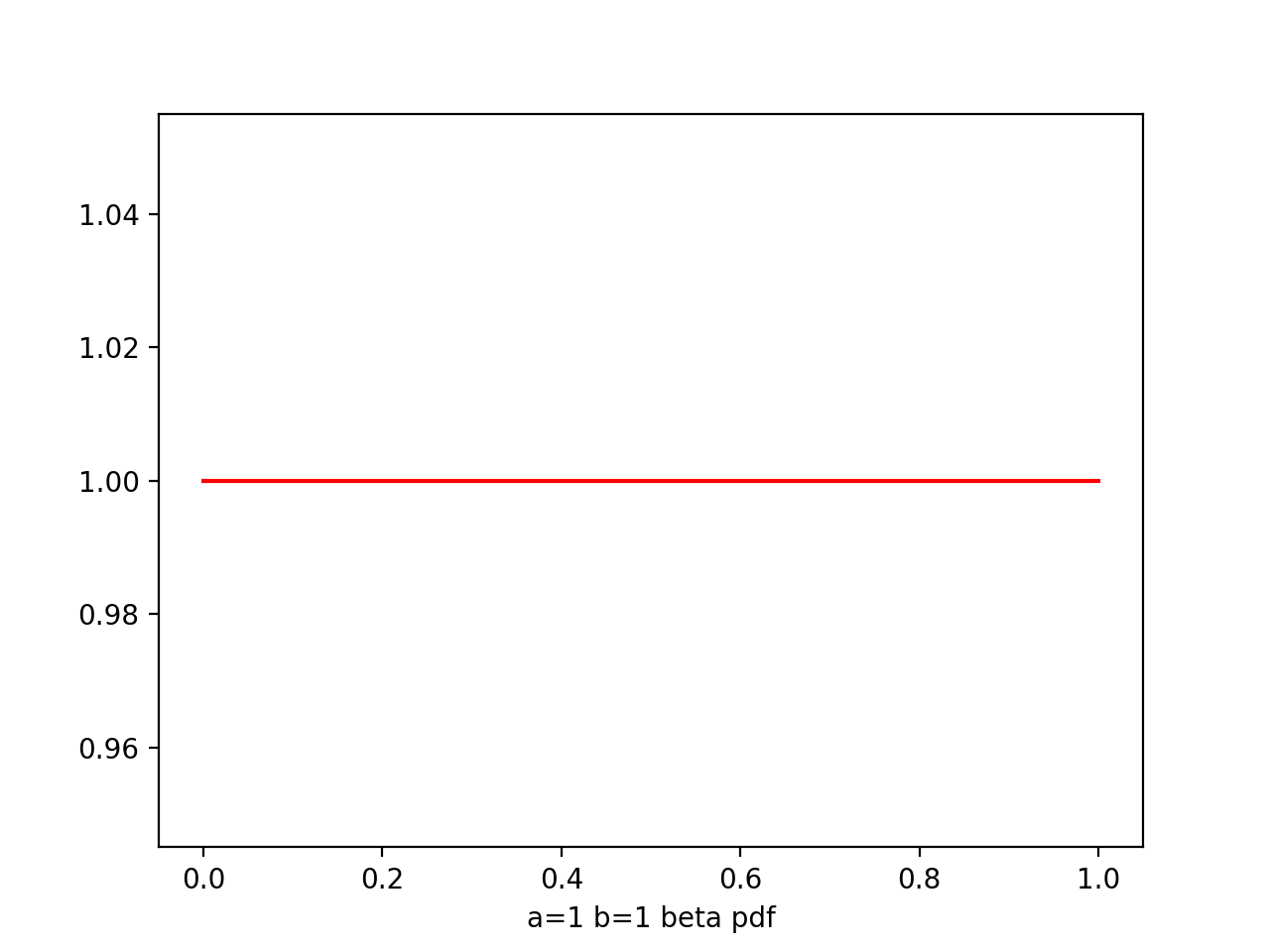

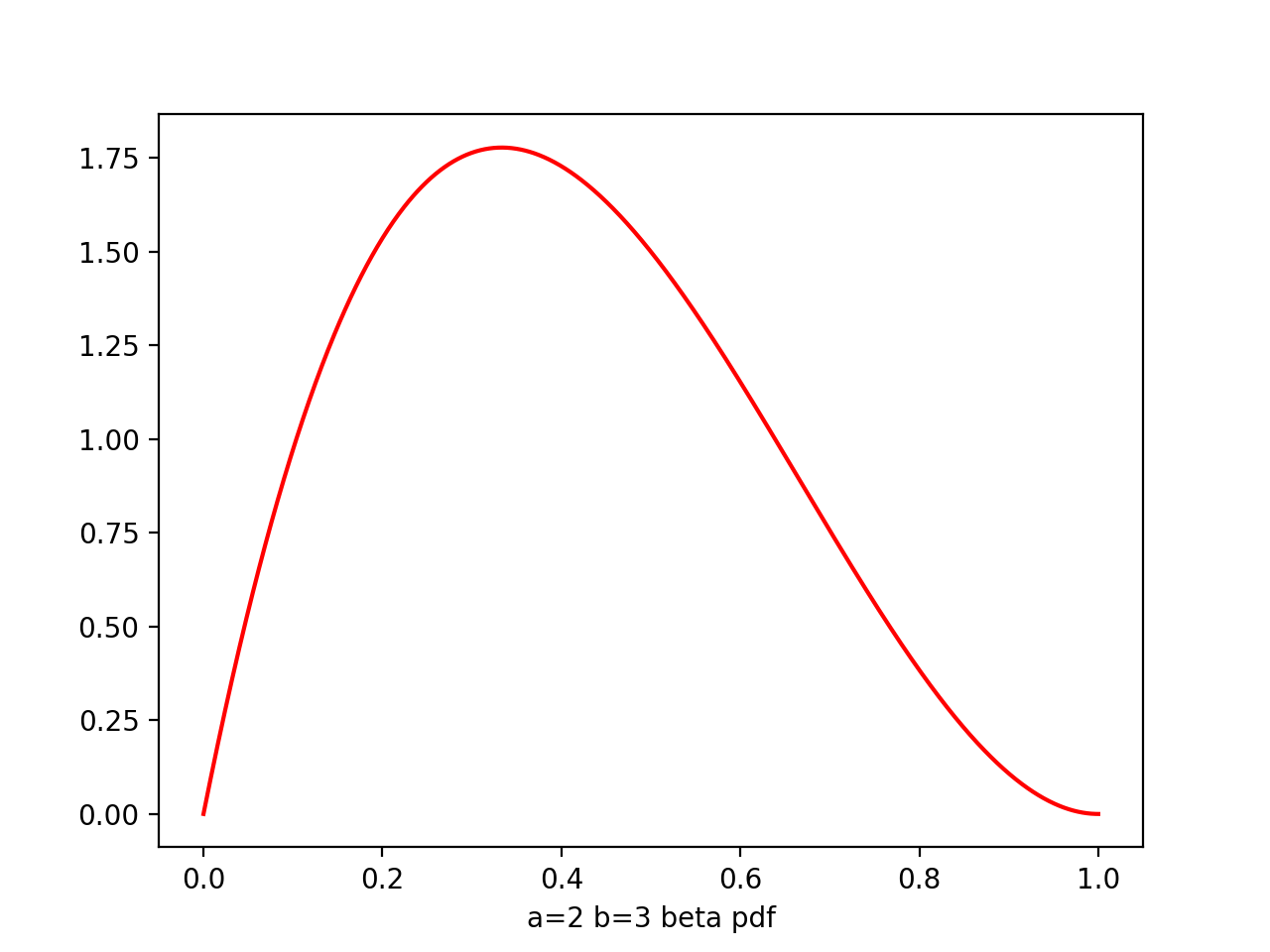

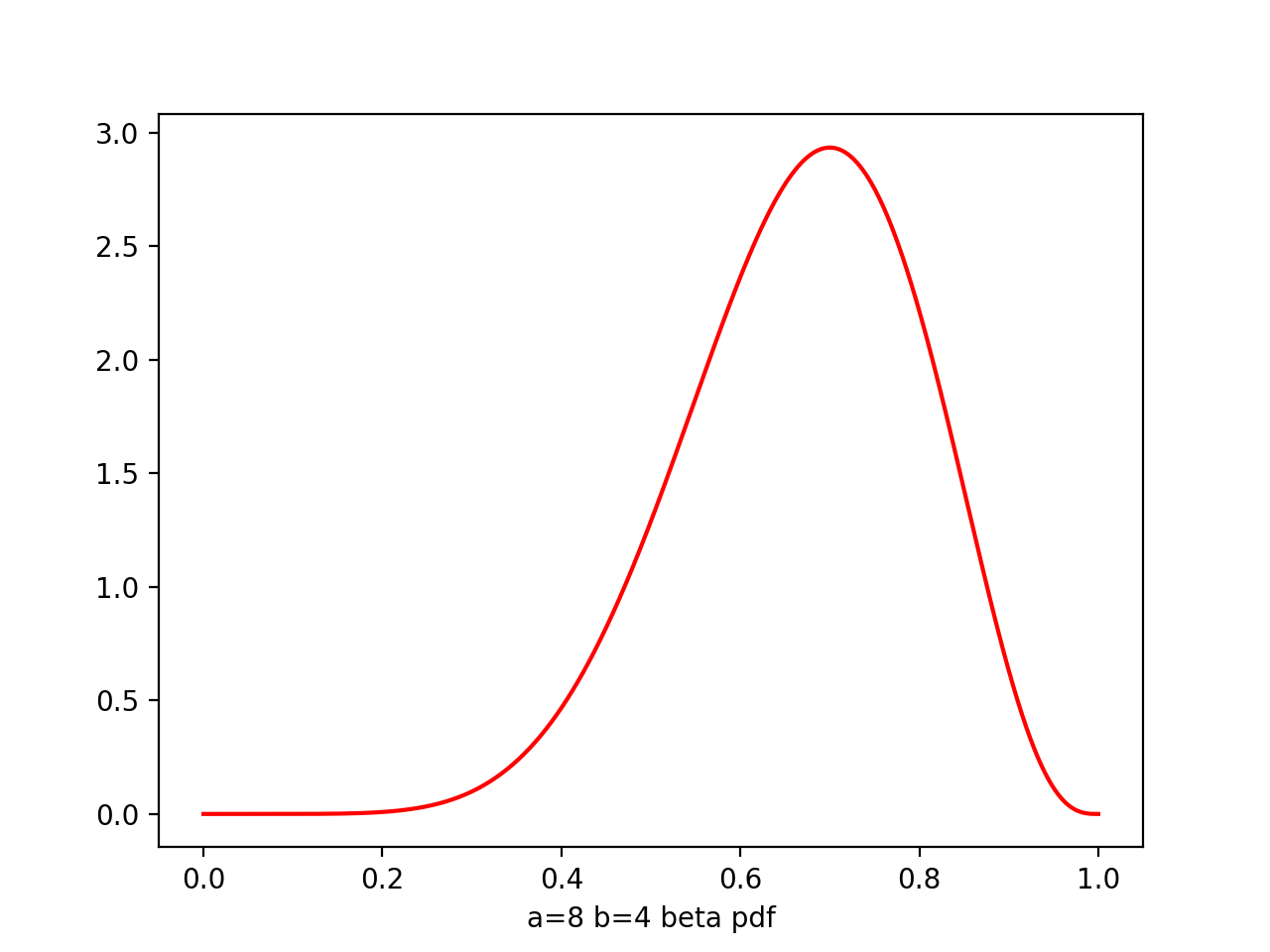

Draw pdf

x=np.linspace(0,1,size=1000)

plt.plot(x,beta.pdf(x,0.1,0.1),'r')

plt.plot(x,beta.pdf(x,1,1),'r')

plt.plot(x,beta.pdf(x,2,3),'r')

plt.plot(x,beta.pdf(x,8,4),'r')

A Whole Bayesian View

The posterior of μ is obtained by multiplying the beta prior and the binomial likelihood

prior:

Γ(a+b)

Beta(μ|a,b) = -------- μ^(a-1) * (1-μ)^(b-1)

Γ(a)Γ(b)

likelihood:

(N)

Bin(m|N,μ) = ( ) μ^m * (1-μ)^(N-m)

(m)

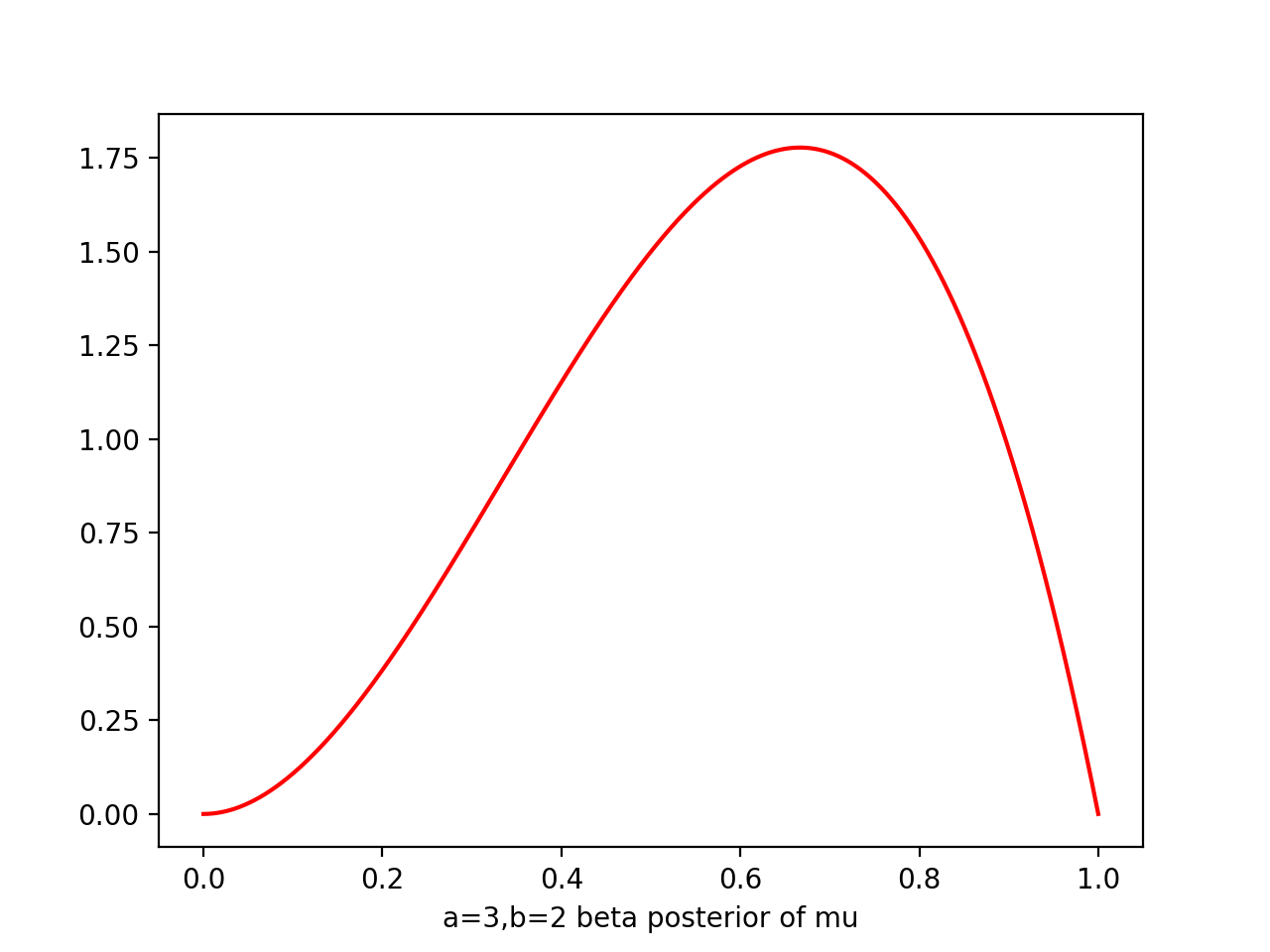

posterior: (keeping only the factors dependent on μ)

p(μ|m,N,a,b) ∝ μ^(m+a-1) * (1-μ)^(N-m+b-1)

The posterior has the same functional as the prior, reflecting the conjugacy properties of the prior w.r.t the likelihood function

Then, the normalization coefficient is

Γ(N+a+b)

p(μ|m,N,a,b) = -------------- μ^(m+a-1) * (1-μ)^(N-m+b-1)

Γ(m+a)Γ(N-m+b)

We can simply interpret a,b are effective numbers of observations of x=1 and x=0

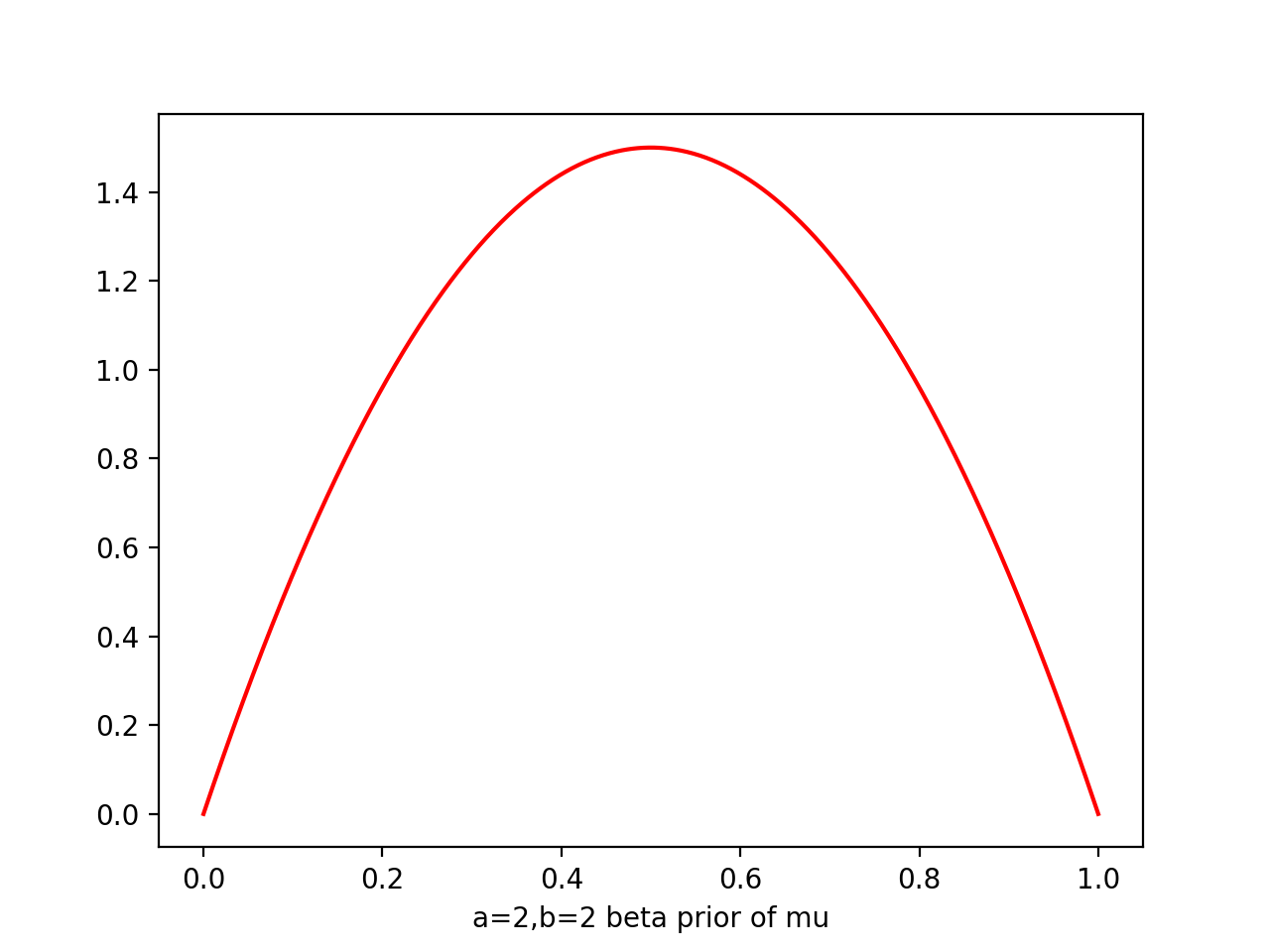

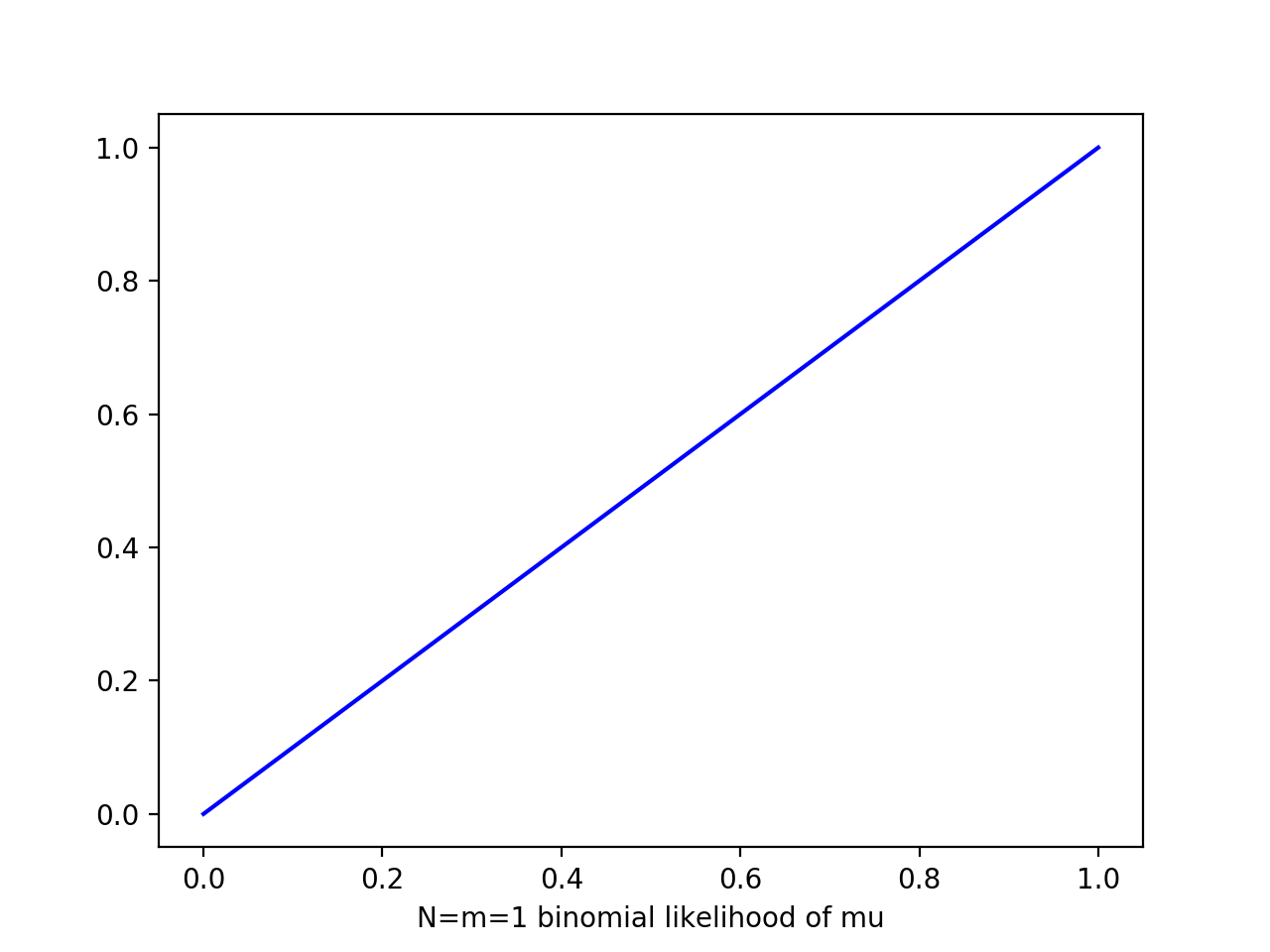

i.e. prior ~ Beta(a=2,b=2), likelihood ~ Bin(N=m=1) => post ~ Beta(a=3,b=2)

x=np.linspace(0,1,num=1000)

a=2

b=2

plt.plot(x,beta.pdf(x,a,b),'r')

N=1

m=1

plt.plot(x,x,'b')

a=3

b=2

plt.plot(x,beta.pdf(x,a,b),'r')

At each stage, the posterior is beta given current observed values of 1s and 0s generated by a,b

observe one more x=1 simply corresponds to incrementing a by 1, and x=0 of b by 1

Sequential Approach

Sequential approaches make use of observations one at a time, or in small batches, then discard them before the next observations are used

(+) real time streaming

(+) do not require the whole data set

(+) can be useful for large data sets

If we evaluate the predictive distribution of x given the observed data set D

1 1

p(x=1|D) = ∫ p(x=1|μ)p(μ|D)dμ = ∫ μp(μ|D)dμ = E[μ|D]

0 0

a Γ(N+a+b)

use E[μ] = ----- and p(μ|m,N,a,b) = -------------- μ^(m+a-1) * (1-μ)^(N-m+b-1) for p(μ|D)

a+b Γ(m+a)Γ(N-m+b)

m+a -> correspond to x=1

p(x=1|D) = ---------

N+a+b

if N->∞, p(x=1|D) = m/N = μ_ML

(infinite (a,b are (exactly the maximum likelihood result)

large small enough

data set) to be ignored)

if N is finite, p(x=1|D) lies between the prior mean E[μ]=a/(a+b) and maximum likelihood estimate 1/N Σ_N x_n

From figure of beta a,b from (0.1,0.1) to (8,4), we see as the number of observations increases, so the posterior distribution becomes more sharply peaked

This can also be seen from var[μ]=ab/(a+b)^2(a+b+1), in which we see the variance goes to zero for a->∞ or b->∞

AKA a general property of Bayesian learning, that as we observe more and more data, the uncertainty represented by the posterior distribution will steadily decrease

Proof of this property

Reference

Bishop Chapter 2 Probability Distributions

Probability Distributions in Python with SciPy and Seaborn

Binomial Distribution: Formula, What it is and How to use it